What If They're Wrong?

I recently came across a blog post by the mathematician Igor Pak entitled "What if they are all wrong?" (2020). In the post, Pak discusses conjectures, mathematical statements whose truth has not been ascertained. They could be true or false (or undecidable), though generally the person proposing the conjecture believes that statement to be true. Pak explores why mathematicians care about conjectures, what makes certain conjectures interesting targets for mathematical research, and the (under-recognized) value of attempting to disprove a conjecture.

I'm a chemist, not a mathematician, and even for chemists I'm not particularly good at math. Nonetheless, I have a casual interest in mathematics research, which initially drew me into Pak's writing. But as I read, I felt a familiarity, something about Pak's arguments that resonated with my views on and experiences with chemical (scientific) research.

This blog post is my attempt to develop those feelings into a more coherent form. I'll discuss the process (and the joy) of searching for the places where the scientists of the past have gotten it all wrong. My analysis will focus on the idea of chemical mechanisms, which, as I'll explain, have some similarities with mathematical conjectures, both in form and in their social function in the research environment. I'll give some reasons why you might want to become a "mechanism hunter" like me, seeking out questionable mechanisms and trying to support or falsify them, and towards the end I'll provide some (hopefully practical) advice to consider as you study these chemical conjectures. Reading Pak's post before this one is not necessary, but it is well worth the read.

What's In a Mechanism?

Preparing to write this post, I wanted to make sure that I was thinking about mechanisms in a clear and consistent way. I was intrigued to find that the idea of "mechanism" has been of recent interest in the field of philosophy of science. Thinkers have been pondering mechanisms, from what they are (and are not) to why they're important in science and how they're developed. In this discussion, I will start from the following definition that has somewhat recently found widespread use:

A mechanism for a phenomenon consists of entities (or parts) whose activities and interactions are organized so as to be responsible for the phenomenon.[1]

To parse that out slightly, when one posits a mechanism, one is suggesting a set of actions (the "activities and interactions" of the "entities (or parts)") that, taken together in some way, cause some observed behavior ("phenomenon") to occur. And to make this even more concrete, I will provide a chemical example. In a reaction mechanism, the "phenomenon" being caused and explained is the reaction outcome — the formation of some product, the decomposition of some compound, etc. The "entities" are the reactants and intermediates that are required to lead to the observed outcome, or alternatively, the individual reaction steps that together make up the overall observed reaction. There's a lot more to mechanisms than just this definition, but it'll be enough for our purposes.

Mechanisms in chemistry (and, probably, in other sciences) begin their lives as conjectures. A researcher observes some behavior, but they (or their advisor, or the reviewers of their manuscripts) are unsatisfied with the observation alone. Rather, they demand to know why that behavior occurs. The "why" — the explanatory mechanism — is more than a cherry on top. Understanding why something occurs can help the researcher place an observation in the context of a coherent theory, and this might enable future predictions and developments based on the initial observation. The observation of electron ejection from metals upon irradiation with light was an interesting empirical development, but it was Einstein's explanation of this phenomenon (the photoelectric effect)[2]via quantization of light/energy that would eventually lead to (among other things) the invention of photovoltaic devices such as the now-ubiquitous solar cells.

To answer the question of "why", our researcher searches for a mechanism that plausibly explains the behavior that they observed. At this point, we are squarely in the realm of conjecture. And, just as in mathematics, a good researcher will then try to convince themselves and their colleagues that their mechanism is correct, or else try to come up with a better one.

Chemical Conjectures

Most areas of chemistry do not have the luxury of proofs. We cannot, through logic and careful argument, remove all doubt that our ideas are correct. Instead, we must be satisfied with models that are inevitably flawed (but perhaps useful) and arguments that are at best consistent with the available data. However, we can disprove. As the eminent philosopher of science Karl Popper argued, hypotheses and theories can only be considered scientific if they are falsifiable, i.e., they can be contradicted by empirical evidence.[3]

Given the importance of counterevidence to the testability and legitimacy of scientific ideas, one would think that disproving ideas would be a cornerstone of scientific praxis. Pak's original post provided a quote (also from Popper) summarizing this notion:

[Great scientists] are men of bold ideas, but highly critical of their own ideas: they try to find whether their ideas are right by trying first to find whether they are not perhaps wrong. They work with bold conjectures and severe attempts at refuting their own conjectures.[4]

I'll put Popper's gendered language aside for the moment and focus on the sentiment. Perhaps his assertion is true when a mechanism can be straightforwardly confirmed or refuted by experiments. If that is the case, then it would simply be lazy not to do the extra work to see if one's conjecture is false. However, many mechanisms are not so easily dismissed, either because it is extremely difficult to gather evidence necessary to refute a mechanism or because the evidence that one can gather is only indirect. If you believe that the performance of your optoelectronic device is hampered by defects, you can go looking, but measurements of defect concentrations are notoriously difficult. If you posit a reaction mechanism, you may be able to look at kinetics or distribution of reaction products to support or refute your claims. Unfortunately, the transition-states and short-lived intermediates that would serve as hard evidence are most often undetectable, even with the best spectroscopy we have today. In these frequent difficult cases, mechanisms can remain conjectures for rather long periods of time.

Aiming to Disprove

By now, I've hopefully done a decent job explaining what a mechanism is, as well as how and why they function as conjectures. I've also pointed to why researchers may not devote themselves to "refuting their own conjectures" to live up to Popper's image of greatness. Instead of clearing the field and leaving only a handful of stubborn questions for the next scientist down the line to deal with, we chemists tend to litter the literature with conjectures.

But I, like Igor Pak, see great value in disproving conjectures. Pak provides three motivations to pursue disproof in mathematics: opportunism (most folks try to confirm, rather than refute, so one can swoop in on a strong result with little competition), beauty, and construction (disproof in mathematics typically requires a counterexample, which must be designed by the researcher). Opportunism certainly also applies to disproving chemical conjectures, while beauty is perhaps too loose and subjective and construction does not strictly apply (one can demonstrate that a proposed mechanism cannot be true without constructing an alternative, though in practice counterproof often involves constructing a new experiment, a new simulation, and/or a new alternative mechanism).

On top of opportunistic, attempting to falsify chemical mechanisms is an activity that is productive because it is very unlikely to produce nothing of scientific value. In the best case, you find counterproof and get to turn a field on its head. If you don't find counterproof, this will typically be because you have instead found some evidence that supports the dominant conjectured mechanism. This may put a controversy to rest or else might put an even larger target on the mechanism for future researchers. "Mechanism hunting", as I'll call it for the rest of this post, also happens to be a research activity that brings me a great deal of joy and excitement. I (subjectively) find it exhilarating to tear down a faulty structure of logic and attempt to lay down a more solid foundation. That dogged pursuit of truth is a huge part of the reason I became a scientist!

In the rest of this blog post, I'll illustrate the process of the hunt through an example that I somewhat-recently worked on in collaboration with undergraduate Thea Bee Petrocelli.[5] To set the stage, I spent most of my years as a PhD student thinking about electrolyte decomposition in batteries. Readers unfamiliar with battery electrochemistry might be surprised to learn that the electrolytes in lithium-ion batteries are actually designed to break down. Specifically, they're engineered to react in the first few charging cycles in order to form a protective layer (a "passivation film" in jargon-ese) called a "solid electrolyte interphase" or SEI on the battery's negative electrode. Electrolyte decomposition is a make-or-break factor for batteries; a good SEI can enable stable performance for many thousands of charge-discharge cycles, while uncontrolled reactivity can lead to disaster.[6] The focus of my research was to use computational simulations to try and understand exactly what was happening during SEI formation. What components reacted when, and how? How did individual reaction pathways interact to lead to SEI layers with particular compositions, structures, and properties? In other words, my job was to closely interrogate electrochemical reaction mechanisms.

Choosing Targets

In a sense, my job was easy. Inspired by the title of an early review paper,[7] the SEI has been widely called the "least understood" component of a battery, and that mystery remains because SEI formation is an extremely complex, far-from-equilibrium process with many interrelated reactions occurring simultaneously. It's a nightmare to study using either experiments or theory. Everywhere you looked, there were electrolyte components that the community knew (or believed) were reactive, but for which the mechanisms were not well understood. There were also plenty of SEI components and structures that had been observed in experiment but whose origin had not been thoroughly explained.

Given so many options of electrolyte solvents, salts, additives, and impurities, not to mention observed or postulated SEI products, where should one choose to focus? What mechanisms are most interesting, most worthy of our limited time? There are no hard-and-fast rules for developing mechanisms, validating them, or refuting them, but when I'm thinking about research problems, I use the following criteria:

Relevance. How important is the mechanism in question? If you perfectly understood it, what would that allow you to do? In the case of reaction mechanisms in a battery, I thought about how widely used a particular component was and how one might seek to control SEI formation by promoting or inhibiting particular reaction pathways.

Uncertainty. Any hypothesis, no matter how strong or long-standing, could be false, but given limited time and energy, one should focus one's efforts on trying to falsify mechanisms that already appear shaky. Are there multiple conflicting hypotheses related to the mechanism? Does the mechanism rest on explicit or implicit assumptions that may not be valid? Studying a mechanism that is highly uncertain is likely to lead to some interesting results, even if you do not succeed at falsification.

Approachability. Falsifying a mechanism requires that only one part or interaction in the process does not occur as described. Do you see a way to probe any aspect of the mechanism directly? If so, how many aspects? If not, what kinds of indirect evidence could you gather? The more inroads you have to study, the more attractive the mechanism.

Little Salt, Big Problems

The vast majority of lithium-ion batteries on the market today use lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF; see Figure 1) for their lithium-carrying salt. LiPF has a lot of nice properties. For instance, it dissolves well in commonly used organic carbonate solvents like ethylene carbonate (EC); that leads to solutions with high ionic conductivity, which in turn means that you can charge and discharge quickly. LiPF-based electrolytes also form relatively stable SEI layers on graphite. Things aren't all perfect, though; LiPF degrades to form undesirable side products like hydrofluoric acid (HF) and reacts autocatalytically at high temperature, contributing to thermal runaway.

Figure 1: Lithium hexafluorophosphate. Reproduced from DOI: 10.1021/acsenergylett.2c02351, CC-BY license.

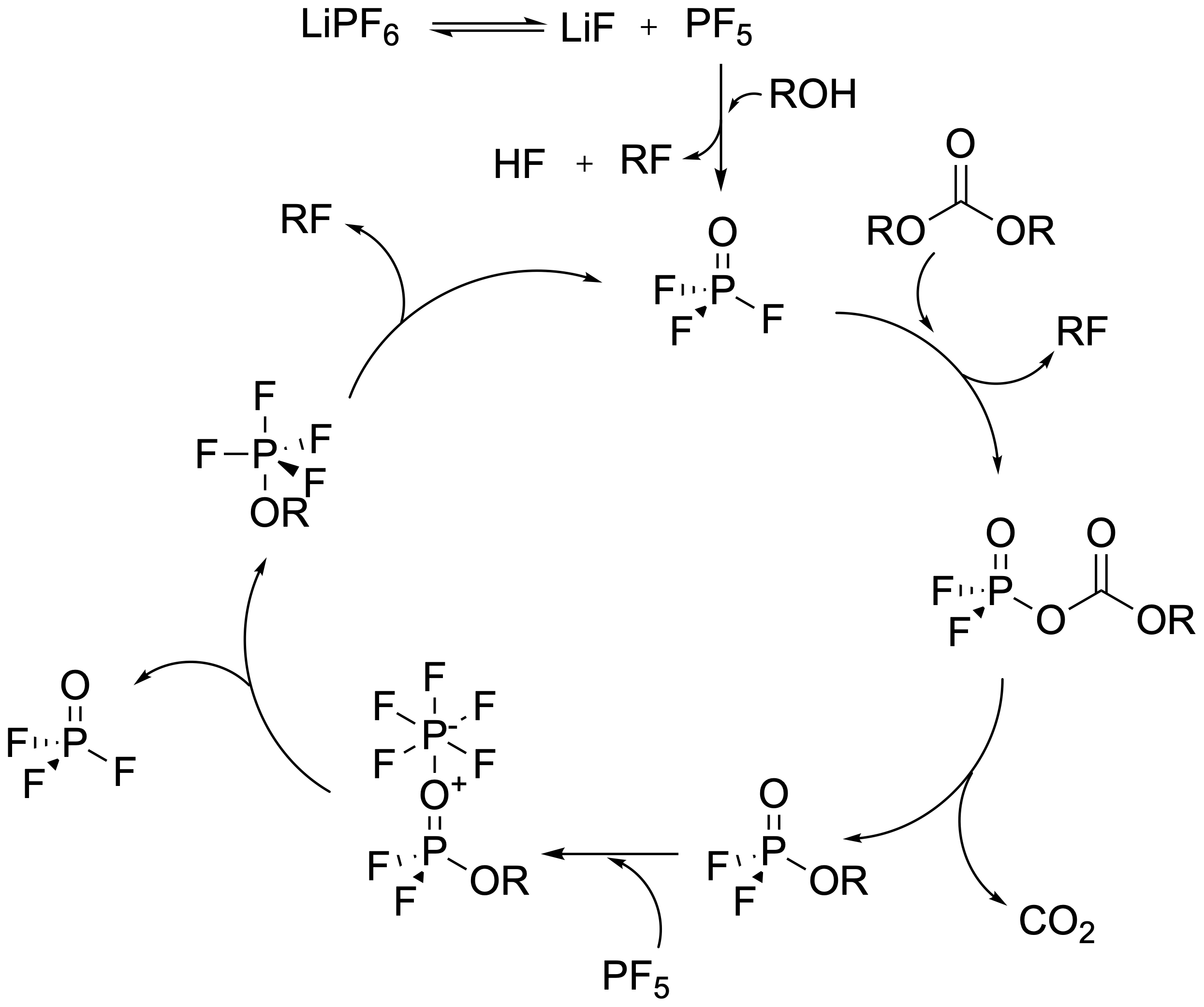

Given the importance of LiPF for commercial lithium-ion batteries, it is no surprise that it had been widely studied using both experiments and simulations. Over the years, a number of mechanisms had been conjectured in the literature. Perhaps the most cited mechanism relied on hydrolysis. It was believed that LiPF would first give up one unit of lithium fluoride (LiF), forming phosphorus pentafluoride (PF). This PF would then react with water — a stubborn, nearly unavoidable impurity in lithium-ion battery electrolyte - to form HF and eventually form products like phosphoryl fluoride (POF). There had also been some suggestion that LiPF might break down electrochemically under oxidizing conditions at the positive electrode.[8] The thermal degradation of LiPF had been far less studied than the initial decomposition related to SEI formation, but a plausible mechanism had been suggested as early as 2005 by Campion, Li, and Lucht (reproduced in Figure 2).[9]

Figure 2: A reaction diagram indicating the formation and autocatalytic reformation of phosphoryl fluoride from lithium hexafluorophosphate, based closely on DOI: 10.1149/1.2083267. Note that this mechanism suggests (incorrectly, as I will show) that POF initially forms from a hydrolysis-like mechanism.

LiPF decomposition mechanisms were the perfect target for mechanism hunting. Given the ubiquity of LiPF, its decomposition is vitally important in the battery industry, and an understanding of how LiPF reacts could conceivably help researchers design additives to promote desired processes (like LiF formation) and inhibit undesired ones (like HF formation). LiPF is a small molecule that could be accurately studied using computational quantum chemistry, and such analysis could provide direct observation of elementary reaction steps including transition-states. And boy, was there a lot of uncertainty around these decomposition mechanisms. After I had been researching electrolyte reactivity and SEI formation for a while, it became clear to me that the reaction mechanisms for LiPF needed to be probed by a critical eye. First of all, in a laboratory setting, electrolytes were often rigorously dried, leaving just trace amounts of water. Could hydrolysis really be the major cause for LiPF reactivity if there was so little water? Even more fundamentally, hexafluorophosphate hydrolysis has been known since the 1960s to be sluggish,[10] and this was supported by more recent theoretical work examining LiPF decomposition in batteries.[11] This evidence alone didn't falsify the hydrolysis mechanism, but it certainly made it sound fishy.

Designing Counter-Proof

Another doctoral student in my research group had tried to study LiPF decomposition using a chemical reaction network approach that we had developed earlier to study EC decomposition.[12] She had struggled to find any pathway that made sense and eventually gave up and moved onto other projects. Thea, who at the time was working with me through the US Department of Energy's Community College Internship program, heard about this and decided that she would be the one to unravel the mystery of LiPF. Thea's internship was only ten weeks long. I was skeptical that they would be able to make any serious progress in such a limited amount of time, and I told Thea as much. At the same time, I encouraged them to follow their curiosity, and together we dug into the problem.

With so little time, I knew that a complex algorithmic approach was not the right path forward. There was too much complexity in the code that we had developed, too many little problems. Besides, building and analyzing a reaction network is a slow process (at least how we were doing it). Instead, Thea and I went at the problem by hand, using our chemical intuition to guide us.

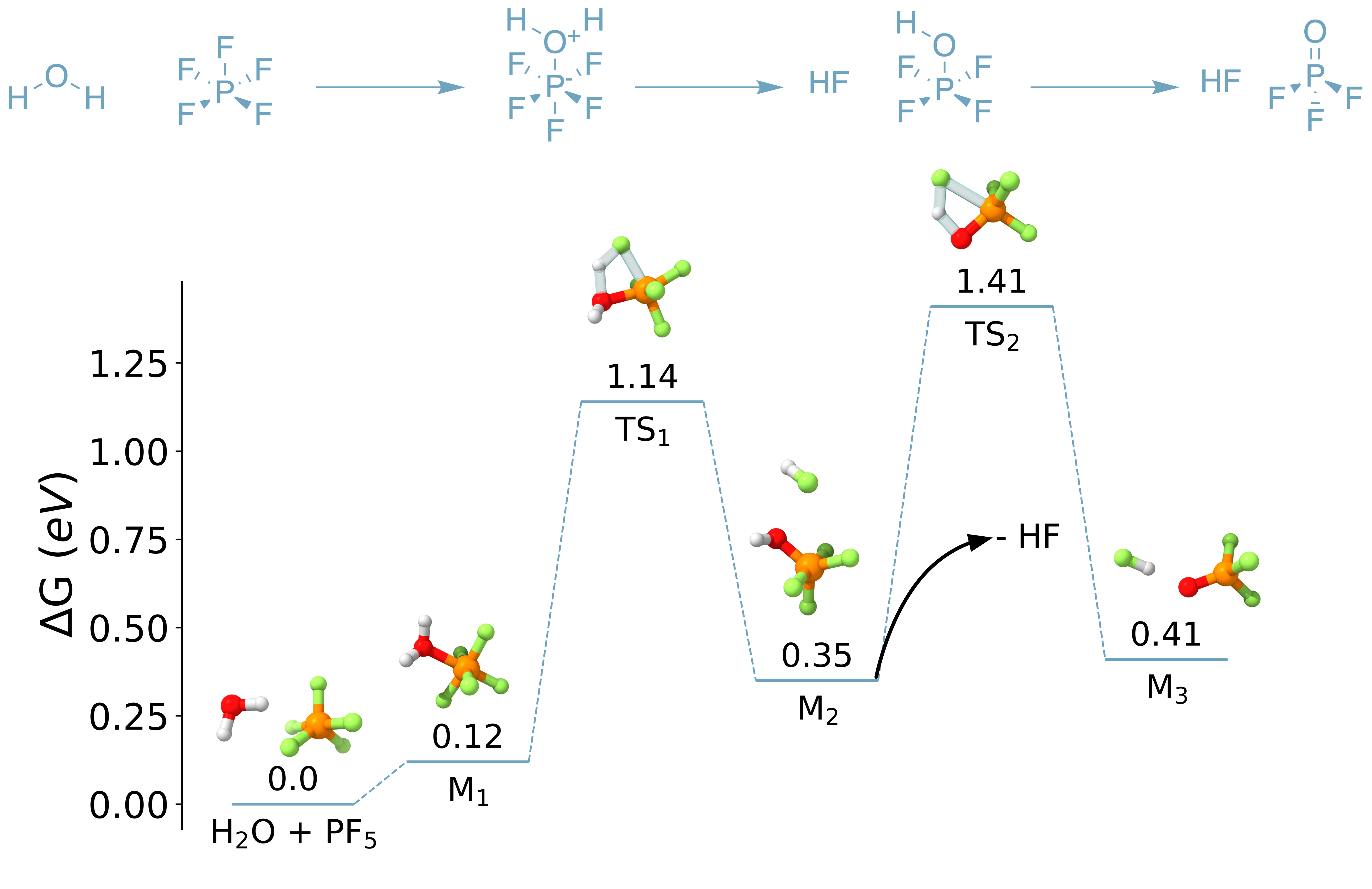

Our first step was to show that the proposed hydrolysis mechanism was too slow to be the major driver of LiPF decomposition. The earlier work of Okamoto had already suggested this,[11] but it didn't hurt to double-check using some more up-to-date methods. This was pretty straightforward. We assumed that the proposed reaction of LiPF to form PF and LiF was correct. LiF abstraction still raised some questions, but there was enough evidence supporting that it occurred that we were comfortable ignoring it. Then, using density functional theory and some clever search and optimization algorithms developed by our collaborators at Schrödinger, Inc., we found all of the elementary steps of PF hydrolysis to form HF and POF (Figure 3). Our numerical results didn't perfectly line up with Okamoto's, but unsurprisingly, we also found that this reaction pathway was way too slow to occur at room temperature. Even worse, we found that every step in this pathway is thermodynamically unfavorable!

Figure 3: An energy diagram for the hydrolysis of PF to POF and HF. Reproduced from DOI: 10.1021/acsenergylett.2c02351, CC-BY license.

Daring Also to Be Wrong

It wasn't enough to say that the LiPF hydrolysis was slow or unfavorable. We had to show that some other reaction with LiPF or PF was fast (or at least faster) and could occur in a realistic battery environment. This was where we had to think outside of the box.

Thea and I went to the whiteboard for hours at a time. At first, we tried to imagine ways that LiPF or PF could react independently at the negative electrode. Could they electrochemically reduce? React with the surface? Could two LiPF molecules interact somehow? When we didn't find anything promising, we expanded our search. This, I think, was the key insight that allowed us to make progress. Previous scholars, likely wanting to keep their mechanisms as simple as possible, had locked in on PF and water in isolation, but this was an unnecessary limitation. We knew that there was much more reactivity going on, and there was no reason to think that LiPF or PF couldn't interact with other reactive species.

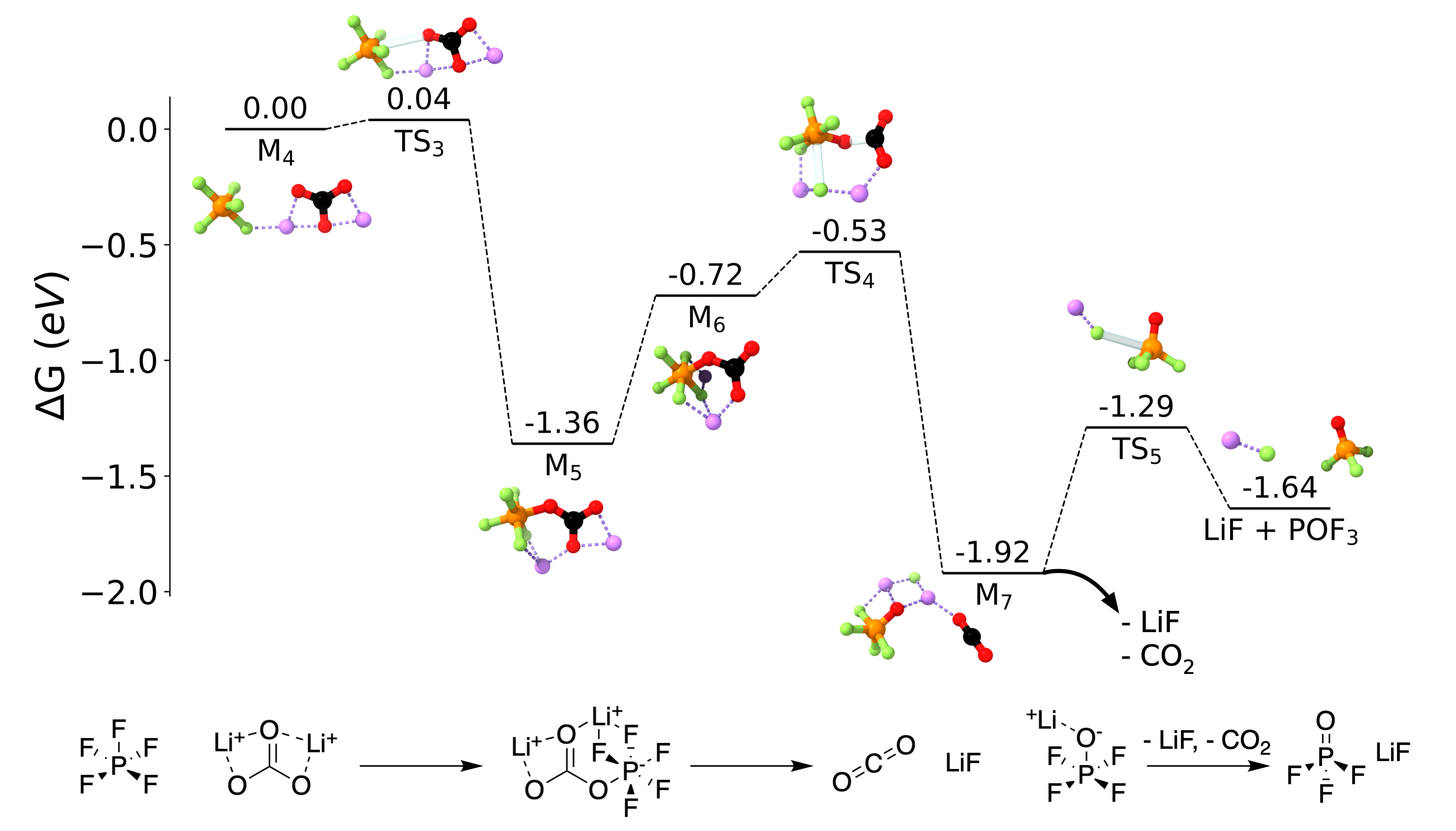

We wrote down every reaction that we believed was happening in the battery along with LiPF decomposition, based on my own studies and other early reports. We made a list of every known or speculated SEI component and considered how each might interact with LiPF and PF, and we settled on lithium carbonate, or LiCO, as a good starting point. Lithium carbonate was small,[13] abundant on both the negative and positive electrodes, and it had a number of sites that we thought might be reactive. Digging back into the literature, we found that there were already a couple of early reports suggesting some kind of reactivity between LiPF and LiCO based on experimental data,[14] [15] which gave us further confidence.

Figure 4: An energy diagram for the reaction between PF and LiCO. Reproduced from DOI: 10.1021/acsenergylett.2c02351, CC-BY license.

Thea went to work on the pathway, again going step by step. If any elementary reaction was slow or severely unfavorable, we had to trash this idea and move on to something else. But Thea's initial results looked good, shockingly good. I double-checked her and filled in the gaps where she wasn't able to find a pathway. In just a couple of weeks, we had something (Figure 4).

It seemed like lithium carbonate explained (almost) everything. Our quantum chemical simulations suggested that PF and LiCO loved to react. Our pathway led to a number of observed products and byproducts, including LiF, POF, and CO, and there were no loose ends or unexpected species. Because lithium carbonate formed from EC reduction, our ostensibly chemical mechanism could still explain the potential dependence of LiPF decomposition, and we didn't rely on any minority species like water. What's more, as far as we could tell, our results were consistent with basically every experimental observation of LiPF decomposition. I was positively giddy; this was an incredibly clean disproof of the hydrolysis mechanism, at least as a major factor in early SEI formation.

As reasonable as our mechanism seemed to us, it was still a conjecture, just like the hydrolysis mechanism had been before. This meant that suggesting it posed a risk to Thea, myself, and our collaborators. What if we were wrong? What if we missed something important, some other critical route that is even more favored, even faster, than ours?

But that's just science. There can be no perfection, and we cannot hold back our ideas for fear of being wrong. Thea and I came up with a bold conjecture, and we tried to find flaws in it. Maybe we're not Popper's great scientists (not least of which because we're not men), but we put in our due diligence. Nearly two years since our the paper was published,[16] I still think that the mechanism that we reported is reasonable. Besides, if we are wrong, I would not want to take the fun of demonstrating that away from my fellow mechanism hunters!

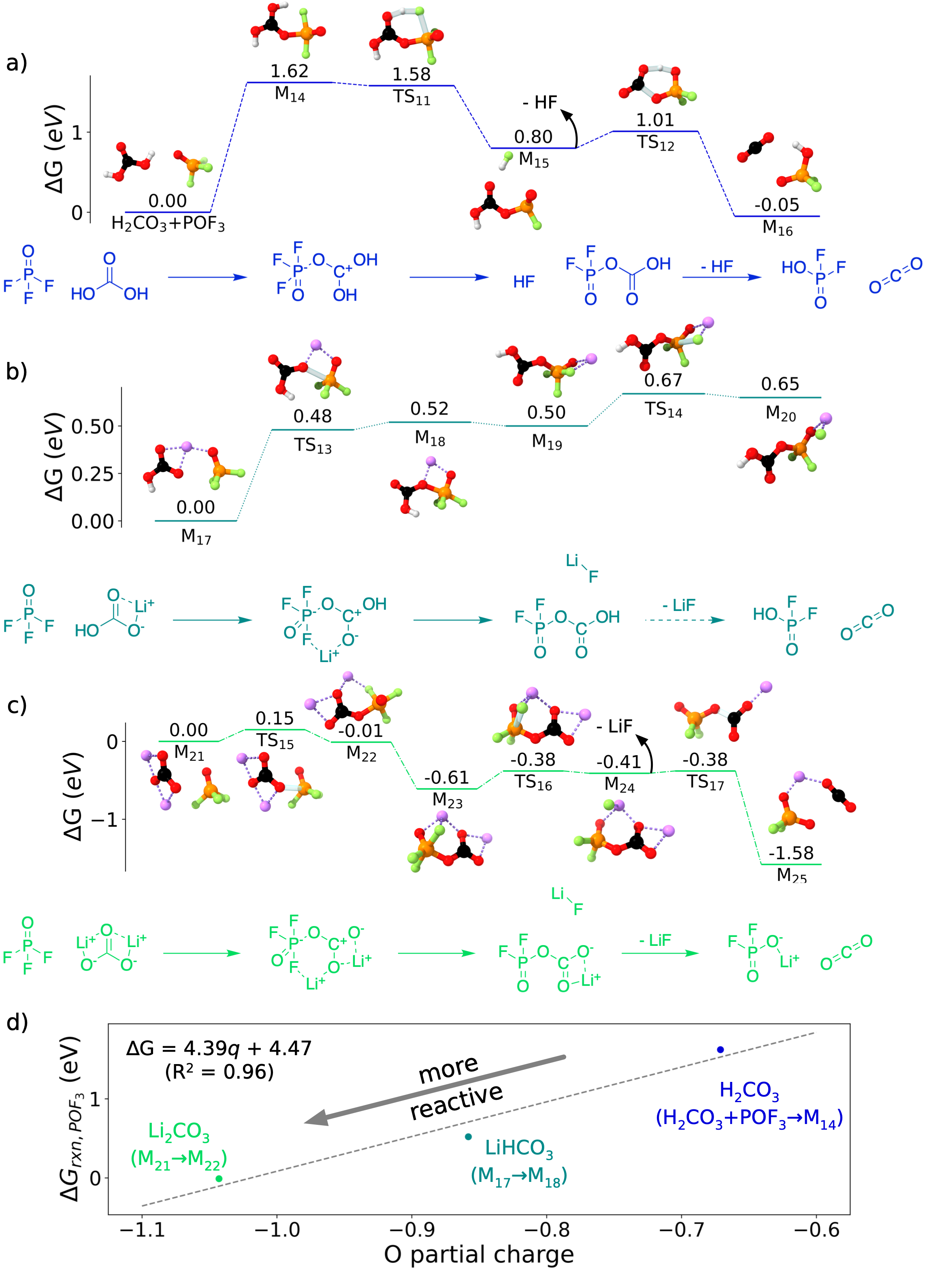

Figure 5: An energy diagram for three reactions between POF and inorganic carbonates a) HCO, b) LiHCO, and c) LiCO. The thermodynamic favorability of these reactions is rationalized in d) via the inorganic carbonate oxygen partial charge, which is a proxy for basicity. Reproduced from DOI: 10.1021/acsenergylett.2c02351, CC-BY license.

Sometimes, They Get It Right

Above, I mentioned that LiPF autocatalyzes at high temperature and that a mechanism for this process had been conjectured by Brett Lucht's group a few decades back. After Thea and I had disproven the hydrolysis mechanism, we thought that we might take a swing at autocatalysis, as well. We had less of a clear reason to think this mechanism was incorrect (this mechanism did not meet our second criterion, uncertainty, very well), but it had not been closely studied by theory since its proposal.

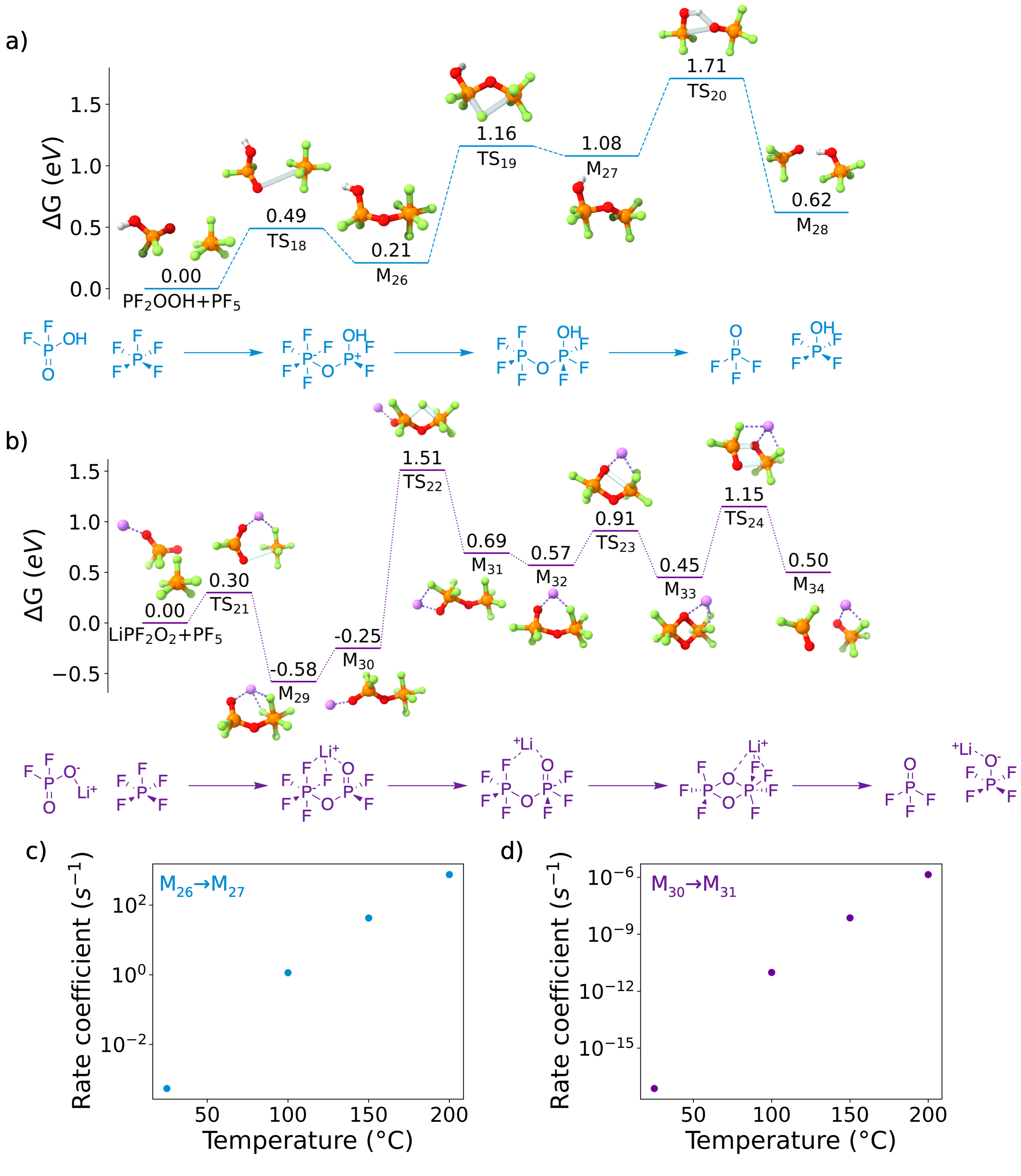

I will spare you the details of our search; suffice to say that we more or less followed the lead of Campion et al., filling in some gaps where necessary and considering multiple (simple) chemical terminations to try and cover our bases. In the end, we found that the Campion mechanism was slightly simplified but didn't have any major flaws (compare Figure 5 and Figure 6 to Figure 2 above).

Figure 6: An energy diagram for the reaction between PF and a) PFOOH or b) LiPFO, formed in the reactions shown in Figure 5. Rate coefficients for the rate-limiting intramolecular fluoride transfer steps are shown in c) and d) as a function of temperature. Reproduced from DOI: 10.1021/acsenergylett.2c02351, CC-BY license.

But even a failed mechanism hunt is still productive, and this is no exception. Thea and I may not have ripped any holes in Campion et al.'s mechanism, but we were able to support this mechanism and find something new to say about it. Specifically, we learned that the reason why LiPF needs high temperatures to autocatalyze is based on one really slow step where a fluorine atom hops from one side of a complex to the other. We also found that the autocatalysis was much easier if protons were involved, which might implicate water (Remember: we found that water and PF react slowly under normal operating conditions. High temperature is a different story!). These results weren't huge deals, but we walked away from our analysis feeling like our time was well spent.

Leaving Gaps Behind

Of course, in chemistry as in many fields, every good answer leaves behind questions. Thea and I did a great job knocking down the hydrolysis mechanism, but we didn't explain everything. The most important question that our analysis left behind involved HF. There's strong experimental evidence that it forms in batteries, and in fact, it can be seriously harmful to a battery's health. Yet HF doesn't show up anywhere in out analysis; what gives?

The honest answer is: we don't know! We're pretty confident that HF isn't coming from chemical reactions with water, and earlier reports of electrochemical HF formation don't seem much better (the calculated oxidation potentials of PF and water, which are usually pretty reliable, are way too high to be relevant to any normal battery).[8]

Some scientist more clever or more dedicated than me will, in all likelihood, eventually cook up a reasonable mechanism. Maybe it'll be you, dear Reader. And when they (you) do, I'll be overjoyed! There's no shame in leaving questions for someone else to answer, in my opinion; quite the opposite. As I wrote in the dedication of my dissertation: "to the brighter minds who will prove me wrong and find better paths than I could dream up. I left you plenty of fuel. Find something fun to burn."

What Should You Do?

So you want to be a mechanism hunter? My advice to you would be this:

Look at every mechanism critically. What are the authors assuming? What evidence do they use to support their mechanism? Does the mechanism appear to be in contradiction with any evidence that you're aware of? Remember that conjectures, even ones put forward by leading experts, are disproven all the time.

Find the gaps in analysis. What haven't previous studies considered about a given process? Can you think of experiments or simulations that you could use to make initial probes of the conjectured mechanism?

Understand yourself Here, I'm once again shamelessly stealing from Pak's post. Every scientist has a specialized set of tools and techniques that they're familiar with. Once you've found a problem worth studying, consider if and how your tools might be used to study it. Just because you've found a mechanism worthy of attack does not necessarily mean that you should be the one to attack it. Save your energy for the tasks you are best suited for.

Make conjectures, but make them carefully. Aspire to be like Popper's scientist, and try to refute your own ideas before you release them into the world. You may still be wrong, but if you are, you can hold your head high and say that you did what you could to explain.

Fear not incorrectness. Absolute proof in the chemical sciences is rare and elusive. Even your best, most solid mechanism might be flawed, as might your attempts to confirm or falsify someone else's mechanisms. You gain nothing by being timid and holding back. Even if you are wrong, by giving into fear, you take away other mechanism hunters' fun.

Footnotes

| [1] | DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198779711.001.0001 |

| [2] | DOI: 10.1002/andp.19053220607 |

| [3] | DOI: 10.4324/9780203994627 |

| [4] | From "Replies to My Critics", presented in The Philosophy of Karl Popper, Part 2 (1974). |

| [5] | Thea is applying for PhD positions this year. Look out for their applications! |

| [6] | I picked one news article that had just been published when I was writing this post. Search "lithium-ion battery fire" or "lithium-ion battery explosion" and you'll find plenty more. |

| [7] | DOI: 10.1524/zpch.2009.6086 |

| [8] | DOI: 10.1021/acsenergylett.1c00707 |

| [9] | DOI: 10.1149/1.2083267 |

| [10] | DOI: 10.1016/0022-1902(69)80024-2 |

| [11] | DOI: 10.1149/2.020303jes |

| [12] | DOI: 10.1039/D0SC05647B |

| [13] | Read: (relatively) easy to study. |

| [14] | DOI: 10.1039/C6RA00648E |

| [15] | DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b08433 |

| [16] | DOI: 10.1021/acsenergylett.2c02351 |